Apalachee History of Alabama

Though they called present-day Alabama home for only a few decades, the Apalachee were an important part of the state’s colonial-era history and an important ally of the French during their occupation of the Mobile Bay area. The Apalachees were a powerful and well-organized tribe that traced their ancestry back to the Mississippian peoples who occupied what is now northern Florida and southern Georgia during prehistoric times. They were forced from their traditional homeland in northwest Florida by European incursions, disease, warfare, and resettled briefly among the people of the Creek Confederacy around Mobile in the eighteenth century.

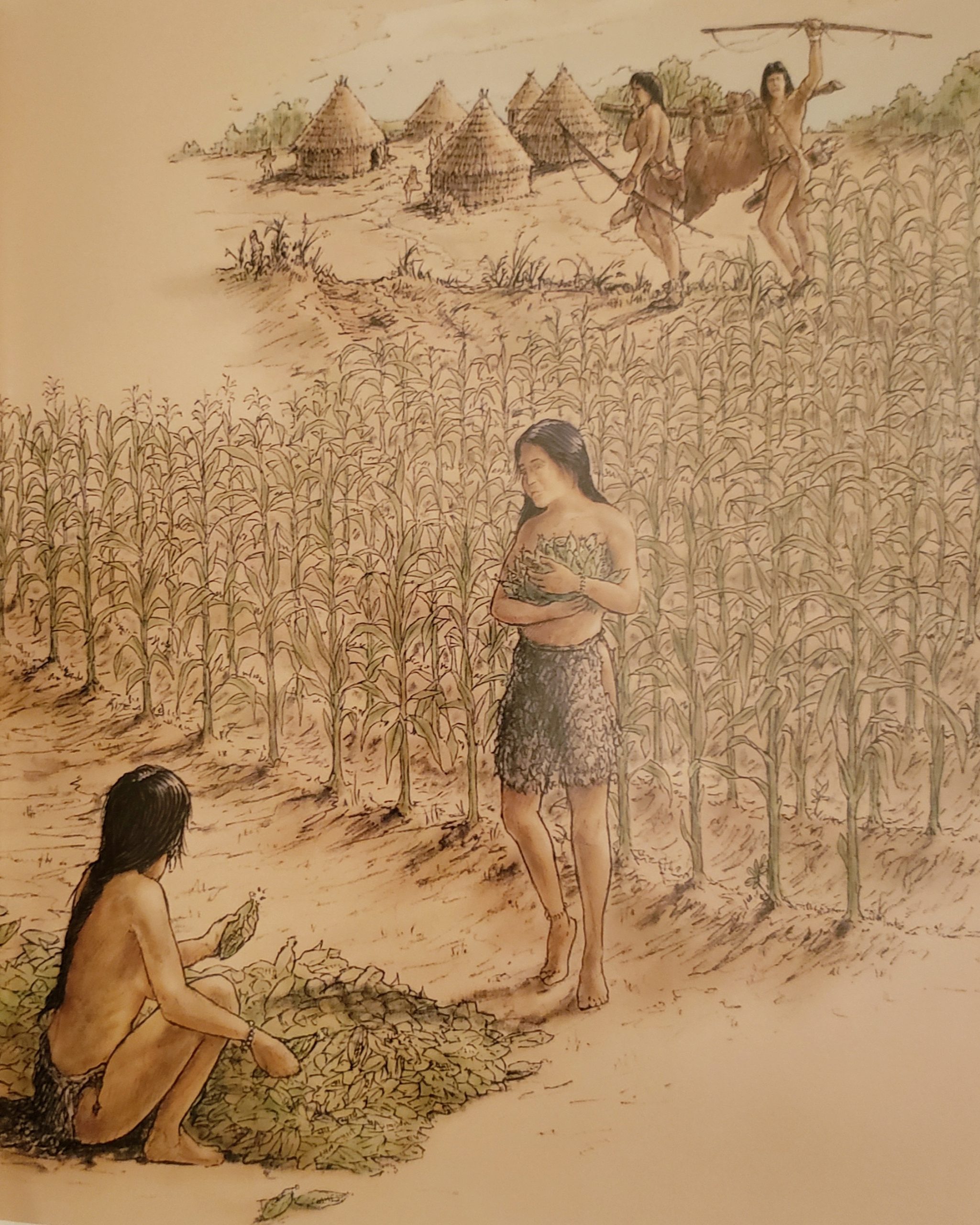

Prior to European contact, the Apalachee lived in highly stratified societies with a complex system of government headed by chiefs, leading warriors, shamans, and counsellors. Like other southeastern Indigenous groups, the Apalachee were a matrilineal society that determined kinship in relationship to the mother’s family. They cultivated corn, beans, squash, and other vegetables and gathered numerous varieties of wild nuts and berries for food. In addition, they fished and hunted animals including bear, deer and varieties of small game. The Apalachees developed a complex religious belief system with using the “ball game” as an important role in social and religious life.

Refuge in Alabama

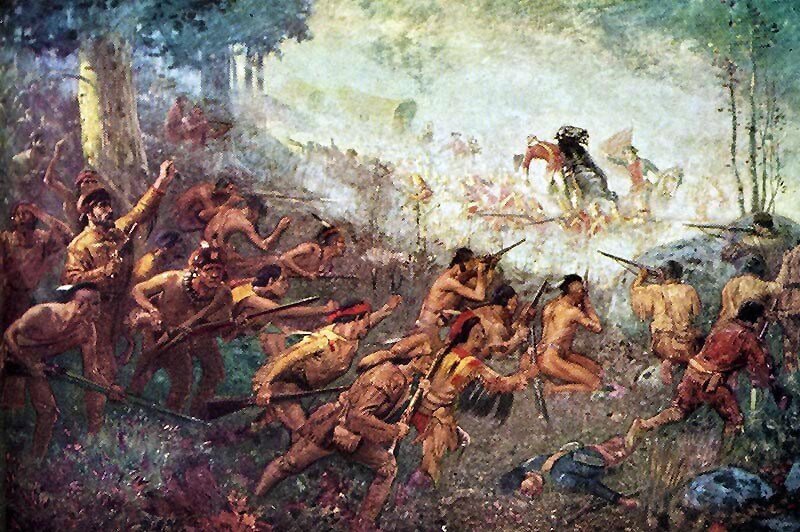

In late 1703, Colonel Moore, no longer governor but still influential in the colony, led a large force of Yamasee, Tallapoosa, and Creek, along with Carolina militia, on what was described as a diplomatic mission to the Spanish presidios on the Gulf side of Spanish Florida. However, Moore, and his assocates back at Charles Towne, were more interested in slaves than peace. Beginning in January 1704, at La Concepción de Ayubale, near present-day Tallahassee, his force of “diplomats” laid waste to the Spanish-controlled province of Apalachee, east of Pensacola, essentially ending Spanish control in the Apalachee region.

The French Governor of Louisiana at the time, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, was properly alarmed by these developments, but he was more concerned about their immediate impact on Mobile. French officials at their newly established colonial administrative center of Mobile encouraged the Apalachees from Mission San Luis de Talimali to settle in the Mobile Bay area. While yellow fever was ravaging the colonists at Fort Louis that was brought in by a ship caring two dozen French women that were to be married off to French settlers at the request of Governor Bienville, the French received visitors from the east. A Spanish Franciscan and chiefs from two Apalachee bands, the Chacato and Talimali, came to confer with Bienville about moving among the French. Some Apalachee sought refuge with the Chacato when their homelands were destroyed. As the British pushed West, the Chacato and Apalachee fled together to Mobile. It is speculation that the Apalachee that had survived with the Chacato were known as the Chacato Band.

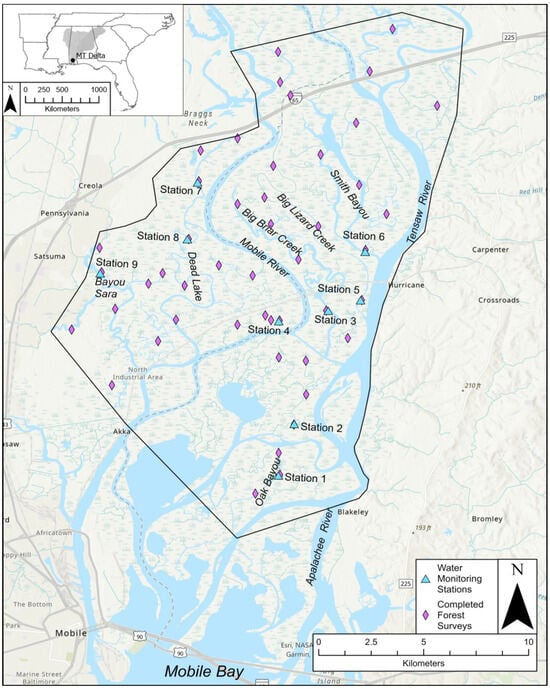

After consulting with his officers, at least those who were well enough to consult, Bienville agreed to assign lands to the Apalachee refugees. He sent the Chacato to the mouth of the Mobile River at a place called Les Oignonets, or “the onion field.” A small band of Christianized Yamasee, former enemies of the Chacato but now peaceful, settled below them. Bienville sent the Talimali upriver to a site between the Mobilian village and the confluence of the Alabama and Tombigbee rivers near present day Mount Vernon.

Other Talimali remained along the eastern shore of the bay across the Mobile Tensaw Delta onto lands that are now part of Historic Blakeley State Park. The timing of the Apalachee arrival at Mobile could not have been worse unfortunately. By the first week of September, they, too, were suffering from Yellow Fever. As the Apalachee were practicing Catholics, they brought their dying children to the fort to be baptized, taxing the strength and the patience of the three remaining priests, who themselves were suffering from the illness. Fathers de La Vente and Huvé, in fact, were still too sick to minister to anyone, so Father Davion had to perform the sacramental rites. There also was the language barrier. No one at Mobile, including Bienville, understood the Muskogean dialect of the Apalachee. These Indians knew Spanish, of course, but the French priests, oddly enough, had not mastered that language (these were Seminary priests, not Jesuits). Among the officers at Mobile, only Châteauguay spoke Spanish fluently.

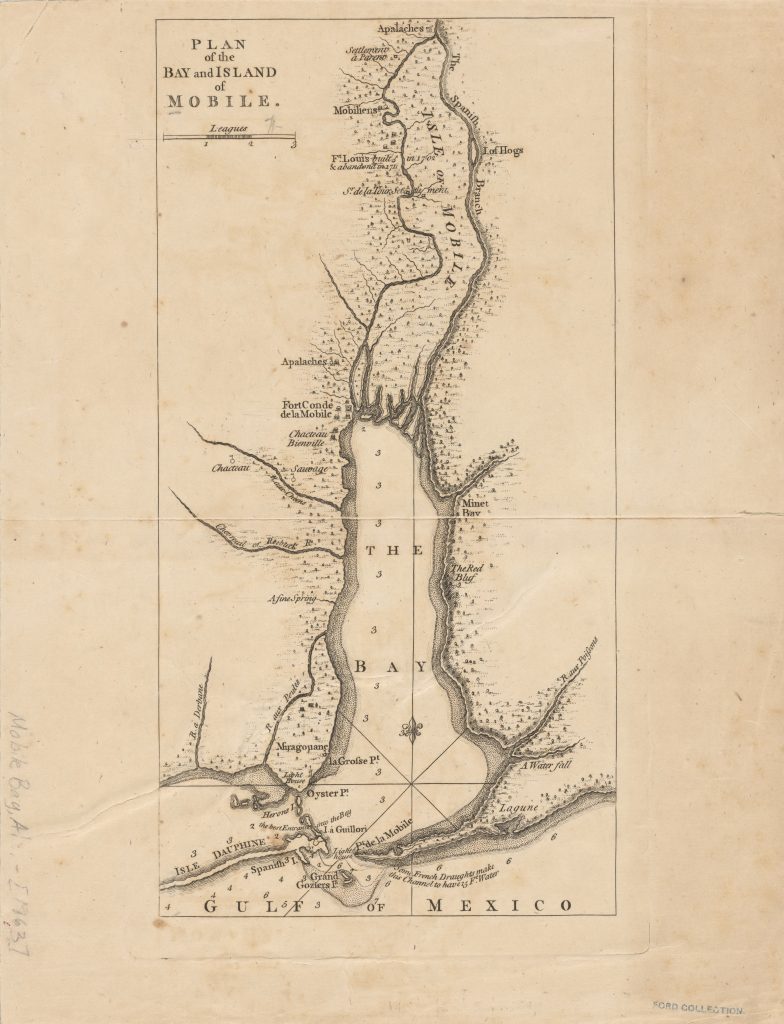

By Spring of 1705, more of the Apalachee, this time the Escambe Band, appeared at Fort Louis, asking to join their fellow Apalachee on the bay. Here was a first bone of contention between the Bourbon allies. The Spanish was determined to restore control over the Apalachee district, so they were not happy to see “their” Indians going over to the French. In a report to the Minister, Bienville explained why the Apalachee preferred to live near the French: “… the French assisted their allies better than did the Spanish, the French furnishing more arms,” Bienville insisted, “in addition to the fact that the natives were not masters of their own wives while among the Spaniards and that among the French they had no fear on that point.” And then there was the question of boundaries between the French and Spanish realms. More than once the issue had arisen between the Le Moynes and the Spanish commanders at Pensacola, first Martínez then Arriola and now Guzmán, who reminded the Frenchmen that a Spaniard named Luna had settled at Bahía Mobila in 1560. The Spanish reasoned that since a natural boundary was needed between their posts, the Mobile River would do just fine. The French demurred, insisting that the entire bay, including its eastern shore, was part of French Louisiana as later they held control of the bay area until losing it to the English in 1763.

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

From The New York Public Library

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/e3ab8950-7c77-0135-fa05-7ffe9ae3ff43

From 1707 to 1710 the region was also under siege from mother nature with hurricanes and record rainfall flooding French settlements of Mobile Bay. During those years, debate and convincing took place whether to move Fort Luis due to flooding issues. In 1711, Governor Bienville finally relented and by mid-May 1711 the co-commanders and a coterie of important officers–Châteauguay, Boisbriant, and Jacques Barbarzant de Pailloux, who had engineering experience–had journeyed down to the onion field to inspect it carefully. The site already was occupied, another testament to its qualities. A few hundred yards to the north of the chosen town site stood the village of the Chacato Apalachee Band who Bienville had given permission to settle there in the summer of 1704. Since their village now would lay too close to the town site, Bienville decided the trusty Chacato should move south to Dog River, their village to stand three quarters of a league above the site of the old warehouse where the river flowed into Mobile Bay. Another Apalachee band, the Talimali, who, like the Chacato, had been granted permission to live near the French in the summer of 1704, would move from their present site on the river between the Little Tomeh and Fort Louis to a new site along the south bank of Rivière St.-Martin, today’s Chickasaw Creek, just above the new town site. Bienville had used Talimali labor to rebuild Fort Louis in 1708 and hoped to use them to help construct the new fort at the Oignonets. Bienville would ask–he could not order–the Mobilian to abandon their ancient village at the fork of the Mobile and Tensas rivers and move downriver to a bluff just north of Fort Louis.

Through the years the Apalachee integrated with the French and other indigenous tribes in the Mobile area. They had their own chapel and priest, participated in the celebrations for the feast day of St. Louis (an important French saint and former king of the nation), baptized their children, and recorded the sacrament in the local diocese registers from 1710 to 1751. They played an important role in the economic life of the community, as well, trading their traditional pottery, copies of European-style earthenware, and a variety of foodstuffs to the French colonists in return for a variety of items including tools, clothing, and jewelry. When many French colonists left this area following its cession to the British after defeat in the Seven Years War (1756-1763; known as the French and Indian War in North America), the Apalachee left as well and established a new settlement along the Red River in Lousiana.

Although the Apalachees’ stay in Alabama was relatively brief, their legacy survives in the form of prominent place names. The Apalachee River that empties into Mobile Bay and Bayou Salome that empties into the Tensaw River. This bayou is named after the wife of an Apalachee chief.